Chapter 2 How God Brought Me to Australia

From 1949 to 1952, I was an apprentice tailor in Judendorf - 'the Jews' village' - near Leoben in Steiermark [Styria] in the heart of Austria. The boss, 3 tailors and I would work 7 days a week.

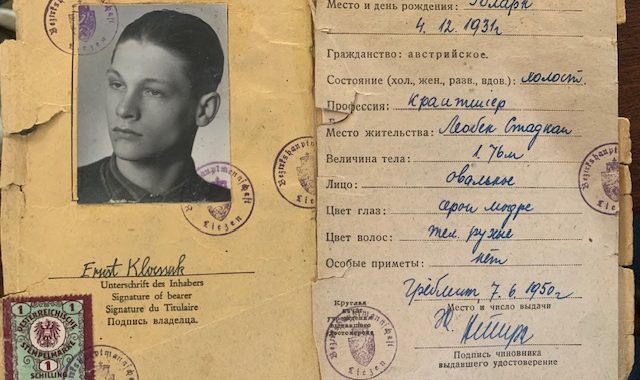

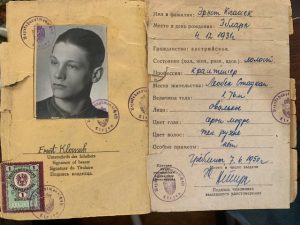

The inside of the identity card with the page for the Russian zone.

One week in mid-winter I got Sunday off, so I boarded a train to take me to the village where I was born. Accidentally, I had gotten off the train at the wrong station, so I had to walk across a field covered by an ankle deep layer of snow to get to a village nearby. Halfway across the field, I met up with a Gendarme - a country policeman carrying a rifle - who asked me to show him my identity card. I searched my pockets, but I couldn't find it, and so the Gendarme frog-marched me to

a police station at the far end of the field. There he and his colleague cross-examined me as I seemed to fit the description of a burglar they were looking for. Finally, they locked me into a police cell with a hard bed and a grey blanket for the night. The following morning, Monday, they took me to a small courtroom, and a magistrate in a black robe told me that the fine for being apprehended without an identity card was . . . an x amount of Schilling. I had no money, and neither my parents nor the tailor shop had a telephone, so the magistrate, doffing his black rimless hat, said, "in the name of the Republic of Austria, I sentence you to 48 hours in custody", and - taking into consideration those 12 hours in the police cell - I had to spend part of the remaining 36 hours in the Gendarme's backyard cutting firewood with a bow-saw. Thankfully, the Gendarme's wife sustained me with a bowl of soup and a bread roll.

With the magistrate's words, "in the name of the Republic of Austria, I sentence you. . ." still ringing in my ears, I decided there and then to get out of my homeland at the first opportunity. And it came after two years working for the British occupation forces, and when they returned to England, I was unemployed.

And so I went to a government employment office, and there on a wall were two large placards, one 'Tradesmen wanted for Brazil', and one 'Tradesmen wanted for Australia'. To apply for Brazil would have meant eventually learning Portuguese, so I asked for and was given a form for Australia.

Until 1972, Australia had the 'White Australia Policy' which meant prospective migrants had to be Caucasian, healthy, and under the age of 35.

Having been given a clean bill of health by an Austrian GP, I was also given one by an Australian doctor. Then I was required to be interviewed by an Australian Consular Official on a certain date at a former refugee camp. When I joined the queue of young men - carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, and blacksmiths - they teased me, "they don't want tailors in Australia". When my turn came, I entered the Consul's office with "good morning, Sir", and the Austrian interpreter looked out the window while I chatted with the Consul. He said, "you should do well in Australia with your grasp of English", and then he looked at some papers on his desk and said, "you have been in trouble with the police - tell me about it". At first my heart sank - here goes my chance to emigrate - but when I told him the whole story behind my 48-hour sentence at a police lock-up, the Consul laughed and said something like, "don't worry, many Australians have convict ancestry". Wow - and when I told the fellows in the queue outside that I was going to Australia, they said, "Yea, we'll believe it when we see it."

The Australian Consul's reassurance that I would be accepted to go to Australia was one thing - to receive it on paper was another - and so I just had to wait, I can't remember exactly for how long, but it seemed like an eternity.

Then, that big envelope from the Australian consulate arrived in the mail! Together with some official papers, it contained a request to report at a former refugee camp at Hellbrunn near Salzburg on a date in June. On arrival at that camp after a short travel by train, I was met by a number of young men who, like myself, were all excited about going

to that vast island continent in the southern hemisphere, with a population of merely 8 million - no wonder migrants were invited by the hundreds of thousands!

After only a day or two in the Austrian camp, we had to board a train on a long trip to the port city of Bremerhaven in north-west Germany. Unlike the sunny Austria we had left, it was grey and overcast up there. The building where we stayed overnight was patrolled by uniformed security personnel, the port area was sealed off by a chain wire fence

with barb-wire on top, and a high gate. Once through the gate, we walked towards the gangway of the Norwegian passenger liner "Skaubryn", and there on the wharf apron was a brass band playing an old sentimental song that brought tears to the eyes of German women about to go on board. The words of the song were, "Muss i' denn, muss i' denn zum

Staedtele hinaus, Staedtele hinaus und du mein Schatz bleibst hier", which translates as verbatim as possible into, "Must I leave, must I leave this little town, leave this little town, and you, my dear, stay here".

As the "Skaubryn" sailed into the North Sea and south, the skies were still overcast, and even the 'White Cliffs of Dover' looked grey. The further we sailed south, the brighter the sky, and when we passed through the straits of Gibraltar, and then along the Mediterranian Sea we had nothing but bright sunshine. Having reached Port Said in Egypt, we tied up but no one could go ashore. Arab vendors in their small boats came as close as they could to the ship's side to sell their wares. The transactions were done with thin ropes let down from deck to the vendors below and back up to the buyers on deck.

The "Skaubryn" then passed through the Suez Canal and sailed into the Red Sea. The skies were blue all around, but suddenly a small dark cloud from Africa came towards us and landed on the ship, covering the bridge as well as the decks fore and aft with a mass of 4-inch reddish-purple locusts. I couldn't help remembering what I had read in Bible-story

books as a youngster - John the Baptist lived on locusts [and wild honey].

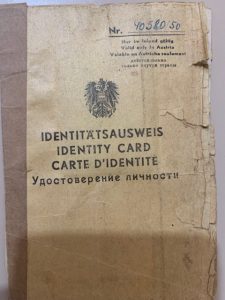

Front of Austrian identity card during the post-war years, 1945-1954.

I'll never forget the night our ship was caught in a storm in the Arabian Sea; we were tossed from port to starboard and from bow to stern for hours, just about everybody below decks became seasick, only a few young fellows like me dared to find a safe spot near the bridge to get some fresh air.

Colombo in Ceylon [Sri Lanka] was our next port of call. Among others, three of us Austrians went ashore. We found the streets largely unhygienic, a butcher had goat carcases at the front of his shop covered in flies, just to mention some examples. We had to take our shoes off before entering a Buddhist temple full of left-facing swastikas. Prior to going back on board, we had a delicious cup of tea with goat's milk at a small venue near the wharf.

Out to sea again. Crossing the equator, there were some celebrations - passengers being dunked in the swimming pool.

On the last leg to Australia, I spent much time with some young fellows on deck with the Norwegian second mate who pointed out a distant elevation in the vast seascape on our port side, and said, "that's Cocos island, - it's not far to Fremantle now".

______________________________

For years, keeping in contact with an Austrian fellow migrant, we regretted that we had not kept a diary to record either our experiences or calendar dates, or both, during our move to Australia. Though we were sure that we had sailed from Bremerhaven at the end of June 1954, and that we landed in Fremantle, Western Australia, near the end of July, we had no date.

God knows all our thoughts and often answers our prayers before we ask. And He did only a few years ago when I was still well enough and shopping at a supermarket in a suburb of Perth. As a lady about my age and I were looking at glass jars of Rollmops - raw herrings pickled in vinegar with onions - she commented about the price, in a German accent, and so I began talking to her in her mother tongue calling those herrings 'Rollmoepse'. Swapping memories about our coming to Australia, she told me that she and her husband had arrived by ship in Fremantle in 1954, and when I asked, "what name?", she said "Skaubryn", and added, "on the 27th of July". She may have noticed my eyes brightening up as I

sent an instant silent prayer of thanks to heaven.

______________________________

The sea just off Fremantle was calm as a millpond. All passengers had to line up at the same lifeboat stations on deck where we had assembled for lifeboat drill during the voyage. We had to bare our arms for inspection by some medics before our ship tied up at the Fremantle wharf.

What a contrast to our port of embarkation, Bremerhaven: There was no chain wire fence with barb-wire on top, no gate, no security personnel, no customs. We just walked down the gangway, over the railway lines and into what turned out to be a quaint 19th century port city! People in town were very friendly, the sun was shining and when I commented about

the warm weather to a lady, she said, "this is our winter".

As my two Austrian friends, one a saw-miller, the other a flour-miller and I walked around sightseeing, the flour-miller asked me to find out whether there was a flour mill in town, and a man told me about the 'Dingo' flour mill and gave me directions how to get there.

At the entrance we were met by the foreman, a Scot. He took us right through the flour mill, and when he found out that one of us was a flour-miller, he offered him a job right away and added, "I got work for your buddies, too". Unfortunately we had to tell him about our obligation to work where the government wanted us for our first two years in Australia. [In reality, however, that obligation was never enforced - typical easy-going Australian]. Back on the street, the flour-miller told us, "they take everything out, all the bran, no wonder their bread is pure white".

From Fremantle we sailed to Melbourne, and a few stayed there while the rest were put on a train. As we travelled, I looked out the window and laughed every time I read a blue-and-white sign close to the railway tracks: ' 5 MILES TO MELBOURNE - DRINK BUSHELLS TEA', '10 MILES TO MELBOURNE - DRINK BUSHELLS TEA', and on and on, and when everybody asked what I was laughing about, I told them about those signs, "these Australians are a funny lot, every 5 miles they tell you how far it is to Melbourne and then they tell you what brand of tea to drink".

When the train stopped - at Seymour? - we were told to go to a peculiar restaurant with small round tables and no chairs near the railway station for free refreshments - big tasty hot sausages, bread rolls and cups of tea. We were wondering what meat the sausages were made of, so I went to the counter and was told, "mutton", and those who were hoping it

might be an unusual kind of pork, I told the German word for mutton, "Hammelfleisch".

The end of our journey took us to a place near Albury/Wodonga in north-east Victoria, a camp of corrugated iron huts called Bonegilla. There was food galore and a big basket of oranges on every dining table. In the big laundry hut we were entertained by Ringtail possums who climbed in on the exposed ceiling beams, and when we reached up and offered them a slice of bread with jam they would lick all the jam and drop the bread. Every migrant received 10 Shilling a week pocket money to spend at the big general store in the centre of the camp - how was that for Australian generosity! Compared to Europe, we had arrived in paradise!

One by one, we were sent to places of employment in the eastern States, mainly New South Wales and Queensland. I was given a ticket for an overnight train to Sydney. At Sydney Central station, a government official took me by taxi to a migrant hostel in South Cronulla. all free! The hostel was such an idyllic spot on the shores of the Pacific Ocean - I felt like staying there forever. Full board per week, with 3 meals a day was 4 Australian Pounds. My weekly pay after tax was 12 Pounds. I had 8 Pounds left to spend. I spent 1 Pound to buy brand new work clothes and boots at an Army DisposalS store. It was easy to open a savings account at the Commonwealth Bank. When I told my parents in Austria in a lengthy letter, they were incredulous.

After a year working for the Electricy Commission of New South Wales as a fitter's assistant in suburban Sydney, I made my way to the Burnie district in north-west Tasmania, to be my home for 36 years.

______________________________

Now that we know how God brought me to Australia, we may well ask why?

Well, my parents had unsuccessfully tried to get out of Europe after World War 2 - they were deemed too old, but because of me they were able to come to Australia in their twilight years under the family reunion scheme. About 4 years after my arriving in Australia, God gave me my wonderful Greek wife, and although He had aroused my interest in Greek when I was in Germany as a 12 -year-old, now I was soon able to write out the scripture references in the Worldwide CoG correspondence course in Greek while my dear Domna - to learn more English - was writing them out in English when we studied together at 6 o'clock every morning before our children got up. God called me first, then Domna and my beloved mother, our children grew up in the Church - blessings beyond expectations!

Finally, let us read, and stand in awe of what God inspired His prophet Isaiah to write:

"Remember what happened long ago; acknowledge that I alone am God and that there is no one else like me. From the beginning I predicted the outcome; long ago I foretold what would happen. I said that my plans would never fail, that I would do everything I intended to do. " (Isaiah 46:9-10, Good News Bible)